The

hardest task for any politician is to please everybody. The ongoing debate on

censorship has long been a contentious one, as one’s view of what should be

censored is subjective to the individual’s point of view, and will differ

greatly depending on a person’s personal, political, or religious interests and

motives. When governments step into the censorship debate, it becomes a

difficult task to legally define obscenity in a way pertaining to society as a

whole (7). Many countries already block illegal content through the use

of filtering systems, and society

generally accepts this (1),

but some countries are trying to pass legislation to also restrict access to

sites that contain controversial content like pornography, file sharing, or

politically inconvenient material. Critics of these proposals have raised the

issue of freedom of speech, claiming these measures to be extreme and

oppressive (1; 2; 9; 12; 16).

|

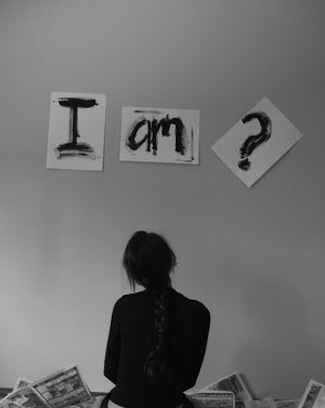

| Fig.1 |

It

seems logical that information inciting or promoting illegal or unethical

practices should be censored. However, coming to an agreeable definition of

what is illegal and unethical is not simple. Pornography and gambling are by

some deemed unethical but are legal in many states and cultures; abortion and

same-sex marriage are deemed ethical but illegal in others (15). One

historical attempt to censor pornography in the USA in 1957 had the Justice

define what was obscene, and the definition included sexually explicit material

appealing to prurient interests, and blasphemy (7). In some countries

this definition would be acceptable, given their religious affiliations, but

not in all.

|

| Fig.2 |

Censorship

which appeases to individual religious interests cannot be deemed proportionate

to society’s interests in general, when a greater extrinsic religious

orientation is linked with lower emotional intelligence (4), and

pornography is found more appealing to people with a higher education (3; 14 cited in 17). Societies

which currently have the strictest online censorship are countries ruled by

authoritarian governments, like China and Iran (9; 12),

who have political views that oppose those of democratic countries (9). Freedom of speech and choice is vital to the survival of a democratic

government (8 cited in 9). Held (2010, p.122) asks

the question ‘is it the Government’s role to determine the value of literary,

artistic, political, or scientific works, and thus prescribe which attitudes or

tastes are valuable and which utterly lack social importance?’, which raises

the issue of how much influence a Government should have on the content of

public media.

|

| Fig.3 |

Staple

Internet services in Western societies, such as Facebook, Twitter and Google,

are banned in China by the Government. There are censored Chinese alternatives,

such as the search engine Baidu, the Chinese equivalent to Google, which are

policed by approximately 50,000 censors. A search for ‘Tiananmen Square 1989’,

for example, will not produce any results about the protest between Chinese

activists and the Chinese army, and the massacre that ensued, saying the site

is nothing more than a tourist attraction. Many Chinese natives, even those who

are tertiary educated, have no reason to doubt the information they find online

through Baidu of its integrity (12). Western society also has this faith

in the quality of information found online, believing that if you cannot find

something on Google or Wikipedia then it must be untrue, unimportant, or does not

exist (13).

|

| Fig.4 |

If

more stringent censorship laws are passed in Western countries, just the

knowledge of the restrictions’ existence could make all those affected lose

faith in the quality of news reports, medical and legal information, and all

other information they find online, fearing that it has been manipulated to

meet Government interests, as is the case in China (1; 2;

12; 15; 16). Google has criticised the

Australian Government’s recent censorship plans, which if implemented would be

the strictest of any Western nation, stating ‘that the scope of content to be

filtered is too wide’, and would result, for instance, in blocking euthanasia,

and gay and lesbian discussion forums, but not pirated media file sharing, or prevent

child luring through chat rooms (1). The US Stop Online Piracy Act,

which aimed to grant the US Government power to restrict access to foreign

sites that host copyrighted material, failed to pass Congress this year after

online protests. Alternatively, in a bid to protect privacy, the European Union

have proposed a ‘right to be forgotten’ that will allow individuals the legal

right to remove online content about themselves that they do not want

available, regardless of the fact they may have voluntarily provided it (2).

|

| Fig. 5 |

|

| Fig.6 |

Pornography

is another favourite target of online censorship advocates, who have suggested

that consumers should have to enrol on a register, kept by Internet Service

Providers, to be able to view online pornography, to prevent youth from

accidentally accessing these sites (16). Not only is the collection

of names of who watches pornography a privacy concern, but youth accessing

online pornography is not done so much by chance as we think. Studies show that

the average male is first exposed to pornography at ten years old (10),

and 16 percent of fourth to eleventh graders have intentionally accessed a

pornographic website (11). When trying to

recruit candidates for a study comparing attitudes of consumers and

non-consumers of pornography, researchers at the University of Montreal failed

to find a single male in his 20s who had never watched pornography (10).

The

omnipresence of pornography in today’s culture makes it serve as sex education

for many young adults, as adults are not always open to discussing sex with

adolescents (6; 17),

though this can have both positive and negative effects. Weinberg, Williams,

Kleiner & Irizarry (2010) found a positive correlation between the

frequency of viewing pornography and a more expansive sexuality, in terms of

what acts were found appealing to watch, and the occurrence of these acts in

their own sexual behaviour. The increased sexual activity, though, was only

occurring with their regular sexual partners, not friends or strangers, meaning

pornography does not promote promiscuity. The greatest effect was on

heterosexual women, who felt empowered by watching sexual acts, with one woman

claiming ‘watching made it real’.

|

| Fig.7 |

The

need for normalisation and empowerment of sexuality is important for people of

all genders and sexual orientations (5; 6; 17), and pornography can enable this, though

mainstream pornography is made by men, and made to appeal to male audiences. If

pornography is to be used as sex education it must also be made aware that

there are many different sexual tastes, that men and women do not always like

the same thing, and that sexuality can reflect many different image types (5; 6; 16; 17). According to Gallop (2009),

We live in a

puritanical double-standards culture, where people believe that a

teen-abstinence program will actually work, where parents are too embarrassed

to have conversations about sex with their children, and where educational

institutions are terrified of being politically incorrect if they pick up those

conversations.

Censorship

of non-illegal content online encroaches on democratic society’s need for

freedom of speech. The implication of banning controversial content would be a

political step backwards, appeasing only to a few societal niches, and not of

utilitarian benefit to the general public. Issues of any controversial manner

should be openly spoken about, instead of being suppressed by legislated

censorship. ‘Censors are, of course, propelled by their own neuroses’ (Justice

W. O. Douglas, 1968 cited in 7, p.127).

REFERENCE

LIST

3- Buzzell,

T., 2005. Demographic characteristics of persons using pornography in three

technical contexts, Sexuality and

Culture, 9, pp. 28-48.

4- Chung-Chu,

L., 2010. The relationship between personal religious orientation and emotional

intelligence, Social Behavior &

Personality: An International Journal, 38, 4, Abstract only, Psychology and

Behavioral Sciences Collection, EBSCOhost,

accessed 17 February 2012.

7- Held,

J. M., 2010. One man’s trash is another man’s pleasure: obscenity, pornography,

and the law. In: F. Allhoff, & D. Monroe, eds. 2010. Porn – Philosophy for everyone: how to think with kink. West

Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. Ch.9.

8- Hirschman,

A. O., 1970. Exit, voice, and loyalty:

responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Cambridge:

Harvard University Press. Pp. 44-45.

9- Krastev,

I., 2011. Paradoxes of the new authoritarianism, Journal of Democracy, 22, 2, pp. 5-16, SocINDEX with Full Text,

EBSCOhost, accessed 31 January 2012.

11- Loughlin,J., & Taylor-Butts, A., 2009. Child luring through the internet, Statistics Canada [online]

12- Margolis,

J., 2011. Great wall of silence, New

Statesman, 140, 5066, pp. 36-39, Literary Reference Center, EBSCOhost, accessed 15 February 2012.

13- Matte,C., 2009. If you can’t find it on Google it doesn’t exist, Quirky Fusion, [blog] 18 April.

14- Parvez,

Z. F., 2006. The labor of pleasure: how perceptions of emotional labor impact

women’s enjoyment of pornography, Gender and

Society, 2, pp. 605-631.

15- Peace,

A., 2003. Balancing free speech and censorship: Academia’s response to the

Internet, Communications of the ACM, 46,

11, pp. 105-109, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost, accessed 18 February 2012.

17- Weinberg,

M.S., Williams, C.J., Kleiner, S., & Irizarry, Y., 2010. Pornography,

normalization, and empowerment. Archives

of Sexual Behavior, 39, 6, pp. 1389-1401, LGBT Life with Full Text, EBSCOhost, accessed 31 January 2012.